I love opportunities that stretch my skills, teach me things, and surprise me. I always pick roles where I would be happy even if I fail. That’s how I’ve managed to be so many things, like engineer, political consultant, university instructor, business owner, and engineering manager. This decision criteria is also how, in the past few years, I found myself straddling the no man’s land between big tech and open source. What I’ve learned through my experiments and interviews is that we have to solve hard problems like supply chain security in open source by changing the criteria we use to make decisions.

Decision making is fundamental to business and leadership, and there is a long list of standard approaches to that process. We work backwards from a north star (or customer experience), make data driven decisions, calibrate on one way vs two way doors, fail fast, OODA loop, and more. I’ve used them all to make important decisions for decades.

The open source community I’ve been a part of argues for a consensus based decision model that addresses all concerns. This approach substantially slows decisions and delivery. It’s the opposite of the fast pace delivered by business decision approaches like failing fast.

There’s also no deference to expertise in open source. The community often doesn’t know the real name of the person who’s raised the concerns they’re determined to address – much less that individual’s experience or education.

Moreover, some open source communities resist having overarching project goals or plans, making decisions based on whether they take the project closer to a desired result impossible. There’s no target experience, use case, or user persona.

As I try to reconcile these two opposing schools of thought into a relationship that can be understood and supported by both groups of stakeholders, I often think of the work of Dr. Victor Vroom, the Yale School of Management (SOM) BearingPoint Professor of Management, Emeritus, and an international expert on leadership and decision making. I was introduced to Dr. Vroom’s work through the Yale SOM Women’s Leadership Program.

When I attended the leadership program at Yale SOM, it included a workshop designed by Dr. Vroom. The premise of the workshop is that Dr. Vroom has identified the ideal model for decision making, and attendees will learn to use it. I was skeptical, and when I sat down to complete the pre-work for this workshop, I was even less confident.

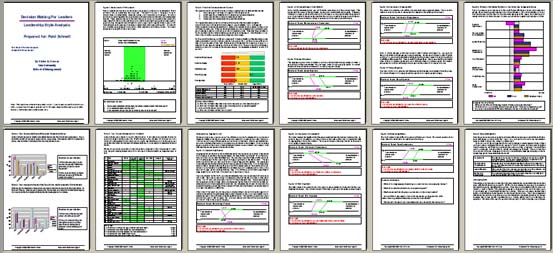

The pre-work presented attendees with 30 leadership scenarios. They’re detailed narratives in which you’re asked to imagine that you’re in a specific leadership role, and faced with a challenge. You’re asked not for a decision, but for the level of engagement you’ll use to decide. You’re deciding how to decide, and there is a spectrum of choices that goes from autonomous decision maker to total delegation to your stakeholders.

After you’ve completed this assignment, Dr. Vroom’s team runs their analysis on each attendee’s responses, who then receive the results as an assessment of their leadership style. The workshop itself is a detailed discussion of the model, so attendees can understand that assessment. Dr. Vroom’s model maps situational variables to engagement models to success rates. That’s where Yale got my attention. Dr. Vroom’s research has yielded a model that can give me the best possible success rate based on situational variables which are relatively easy to evaluate.

The reason this is top of mind in my current role is that Dr. Vroom’s model articulates the differences between business and open source. His situational variables include things like (1) the importance of urgency – how fast do we need to act?; (2) the importance of commitment – how much will stakeholder commitment impact the likelihood of success?; and (3) the likelihood of disagreement – how likely is it that stakeholders will have different opinions? Let’s look at just those three examples.

In business, there is always some urgency, while in the open source community I am part of, there’s never urgency. When I ask open source leaders how long a feature will take to deliver, the answers I get are: “as long as it takes”, “it depends on who’s interested”, or “could be years, we’ll see.” Business investments are a function of the value we deliver for a customer, the impact to the business, and the cost of the work, and all of those values are a function of time. Moreover, time, resources, and scope are the magic triangle of delivery in business, and in open source, none of them are ever well-defined.

Similarly, the importance of commitment in a business decision is somewhere between low to moderate. We know that employee performance is better when individuals are engaged in the decision making process, but we also know that for many decisions, in the absence of other factors (like low job satisfaction), most employees will execute on the work they’re asked to perform. That’s quite the opposite of open source, where the work is a passion project for the people involved. They are volunteers. There is zero possibility of delivery without stakeholder commitment, making its importance very high for even the most trivial things, like how notes are taken and distributed.

Finally, the likelihood of disagreement is just as wide a chasm between business and open source. In business, we hire people with similar skills and values, so while they may disagree on the specifics, they’re largely aligned on principles. In open source, there is very little homogeneity, and the likelihood of disagreement is super high.

In my personal assessment during the workshop, I was told that I react to almost all situational factors effectively, that is, I was deciding how to decide with the likeliest success outcome. The exception to this was “group expertise”. The assessment said that my choices were not affected by the expertise within the group. That’s not to say that I didn’t react to expertise at all. My own expertise was a careful consideration in my decision making.

Now, the attendees of this class are senior leaders from across the globe, and my cohort had questions about these results. We talked about cultural norms quite a bit. Would the model be different outside the USA? Could the model be different in companies with strong, peculiar cultures (like Amazon)? The answer is yes, the definition of success could be different, but the results are largely the same. In other words, some cultures may value speed over correctness. It may be that I was ignoring group expertise, because I work in a culture where speed and delivery are highly valued. We fail fast, get the customer feedback, and iterate.

The next thing we did in the workshop was an exercise in decision making that was far more complicated and less comfortable. The pre-work for the workshop described scenarios like being a CEO with an acquisition, maybe some public relations challenges – very familiar territory. The in-class exercise described a ship wreck that left us on a deserted island with limited supplies and injured and ill passengers. In this exercise, we had to make a series of decisions about survival and rescue.

We did the exercise first as individuals and then formed groups to do the same exercise together. My group was awesome! I immediately took the leadership role, and we huddled in a conference room to work through the exercise together. We finished in the designated time, and everyone in the group felt very good about our performance as a team.

Triumphantly returning to the workshop, our individual attempts to solve the puzzle were scored, and our team solution was scored. That’s when I had my first “aha” moment. Our team scored lower than half of the individuals on the team – on the same exercise! That is, individually, many people on the team did better than our performance as a group. The workshop leaders sent us back to the conference rooms we’d completed the exercise in. Cameras in the rooms had recorded the entire event, and we were asked to watch ourselves to understand where the group went wrong.

This was a life changing opportunity for me, because what I watched myself do – on camera – is shut down “experts” in favor of speed and group harmony. For example, in the exercise, one of the supplies we could choose to carry across the island was tonic water. Since we had planned to travel to a cove with fresh water, we opted to leave the tonic behind. At one point, someone in the group quietly pointed out that one of our passengers was diabetic, and they thought they remembered a diabetic sibling being able to treat a blood sugar spike with tonic. The group had already settled on a supply list, time was running out, and the leader that spoke up didn’t sound confident. I brushed the comment aside and moved on, ignoring the expertise of the group, and killing my fictional diabetic.

Since that experience, I’ve been much more intentional in deciding how to decide. That doesn’t mean that I never compromise or make tradeoffs, but I do so with full understanding of the risk and cost. If we’re going to be successful as an industry with open source, we have to apply the same decision model, intentionally. If we need features delivered on time and with specific scope in open source, businesses need to alter the open source situational factors to enable successful decisions.

We’re doing some of that now. We can create open source teams in our businesses with different situational factors. In my team, the importance of urgency is high, the importance of commitment is moderate, and the likelihood of disagreement is a work in progress as we define an entirely new blended culture. Make no mistake, it’s still a bit of a no man’s land, but I’m getting a lot clearer about why these teams need to exist, and deciding how to decide.